Linear Periodization vs. the Conjugate Method: Which Barbell Training System Works Best?

It’s a good question—and one lifters have debated for decades. Is it the old-school way of linear periodization, where you increase the volume over time by adding weight to the compound lifts in a safe manner, most of the time in a twelve-week program? Or is it the conjugate system, where you do different variations of the compound movements using different equipment such as bands, chains, and specialty bars, spending one day of the week focusing on speed and the other day focusing on max effort?

Well, let's delve into those questions, shall we?

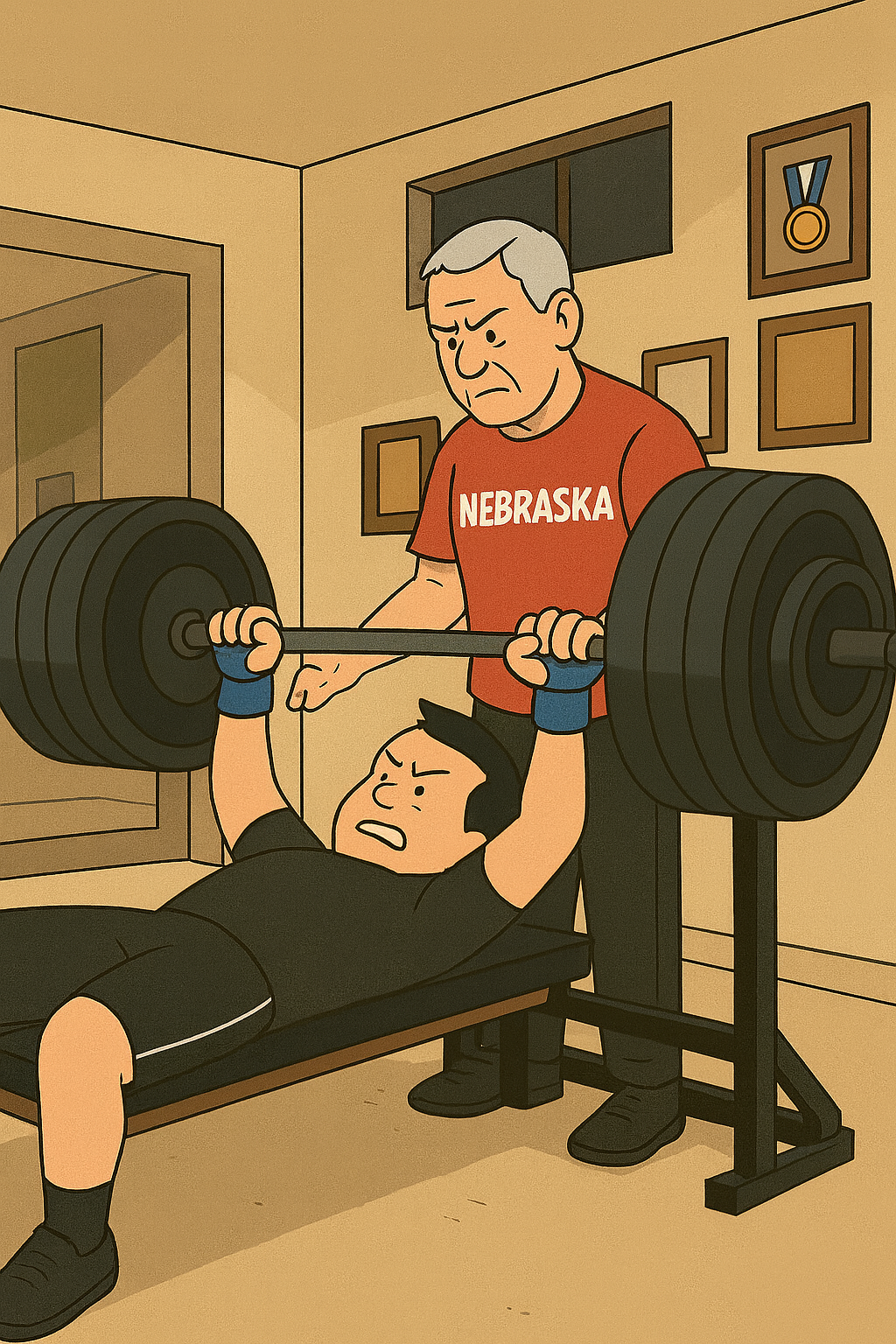

How I Started: My Father’s Influence Understanding Strength and Early Linear Periodization Training

When I started lifting weights, it wasn't in a gym. It was in my parents’ basement, being coached by my father. My dad achieved his best lifts between 1979–1981: a three-times-body-weight deadlift, a two-times-body-weight bench press, a two-and-a-half-times-body-weight squat, and a one-and-a-half-times-body-weight clean and jerk at the age of 19. While participating in the sport of powerlifting, my dad was not a dedicated powerlifter—he was an all-around athlete, spending most of his time playing basketball, softball, and golf. He was a freak athlete with a high vertical jump.

During the 1970s–1980s the popular type of strength training was linear periodization, and that is exactly how he trained me.

Before we talk about how to get stronger using linear periodization, we need to know what strength is. Strength is the ability to apply force on an external resistance. Producing more force allows you to lift more weight, and lifting more weight makes you stronger. We will use the bench press as our example, since it's everyone’s favorite lift. While being coached by my father, he would have me do four sets of five repetitions, then a burnout set with lighter weight. Once I completed that workout with four sets of five and did not fail a set, we would increase the weight by five pounds and repeat until I couldn’t get a set of five. Sets of five repetitions were the bread and butter of the workout.

He had me do this until I got stuck at a 330-pound bench press. He then changed up the program, having me bench three times a week: a light day, a medium day, and a heavy day, while increasing the weight as time went on, normally over a twelve-week program. On the light day he would have me focus on several sets of eight to ten repetitions with lighter weight. This was a lot of volume, and today it would be called overtraining—but we just called it hard work. On the medium day we focused on sets of five with a moderate weight. On the heavy day we did sets of three with heavy weight.

While in my early twenties, this was very effective, but it was a lot to recover from. He normally ran this for about twelve weeks. His program took my bench press from 330 pounds to 405 pounds.

My father strongly believed that to be good at the bench press, you had to do a lot of bench pressing. He did not believe in bands, chains, or other accessory movements to increase the bench press, with the exception of some lat pulldowns and tricep pushdowns. His programming and coaching are the reason I accomplished what I did in the sport of powerlifting. He was not just a coach—he was my first training partner. He did the same program he had me do at the age of fifty-five. If he would’ve competed, he would’ve broken the masters class (55–59 years old) state record by thirty pounds and achieved his elite classification for his age and weight class. The workload he did at his age is the stuff of legend.

While this is not the same program I use for myself and others currently, it worked for me at the time. I am no longer in my early twenties, and benching three times a week with that volume became a lot to recover from and, for most at a high level, would cause injury. I learned so much from his programming that influenced how I program today. I learned what is too much work and what is not enough work, how much work you can recover from, and the value of dedication, willpower, and a strong work ethic. I would not have changed a thing about being trained by my father—it was hands-down the best time of my life.

Experimenting With the Conjugate Method

After my father stopped training at the age of fifty-six, I decided to try the conjugate method. I was always a student of the game, studying different methods of training. Training was not enough for me—I had to research everything possible about how to get stronger. During my mid-twenties, the conjugate method was in style for most lifters.

Using the bench press example again, I would bench two times a week with seventy-two hours between sessions. One session was a speed day or dynamic effort. I used seventy percent of my one-rep max and lifted the weight as fast as possible, trying to get from my chest to lockout in under one second, increasing speed and explosiveness. The variation of the bench press changed week to week. Sometimes I had thirty pounds of chains attached to the bar or bands that equaled ninety pounds, as long as it totaled seventy percent of my one-rep max. Sometimes I used a different bar altogether, like a football bar or a board press.

On the second day, seventy-two hours later, I did a max-effort day. I picked a max-effort lift, sometimes involving specialty bars or movement patterns like a floor press, board press, banded bench press, reverse-band bench press, decline bench, incline bench, wide-grip bench, or close-grip bench, sometimes with bands or chains. I would build up to a one-rep max for that week.

While doing the conjugate method and constantly maxing out every week, my 405 bench press went to 430 pounds. It helped me get used to handling heavy weight. But while all of my max-effort lifts were going up, and my speed and explosion increased, I had a hard time increasing my actual bench press beyond 430 pounds. I found myself stuck again and looking for answers. I felt I was getting better at other bench-press movements but not necessarily the bench press itself.

Returning to Linear Periodization—With a Twist

Reaching out to my father for ideas, I went back to my bread and butter of linear periodization, benching only two times a week—sets of five reps on the light day and sets of three reps on the heavy day, increasing the weight over time. But I added a twist to the program and used some of the lifts I learned from the conjugate method as accessories or tricep work after the bench press. While not doing as much volume as before, my bench went to 440 pounds, then soon after that to 450 pounds as a lifetime drug-free raw lifter, achieving far over a double-body-weight bench press.

The Takeaway: Linear vs. Conjugate

So what’s the takeaway from all this—linear periodization or the conjugate method? It is important to know who is doing the program and what your goals are. In my opinion, linear periodization is superior in every way. Doing sets of five repetitions and increasing the weight over time works every single time it is applied and is the best way to get stronger. Sets of five will stand the test of time. From the 130-pound female who has never touched a barbell and is trying to pass the strength standard to become a police officer, to the college athlete looking to increase their strength for their sport, to the older client trying to get stronger to function better—you cannot go wrong with linear periodization.

Even for top-level powerlifters, linear periodization was the gold standard for years, and I would say it is all that is needed for most competitive lifters. I am not saying conjugate doesn’t work, because it does. It will make you faster and get you used to handling heavy singles. There is an endless amount of variations and lifts. But I truly believe that to benefit from the conjugate method, your lifts need to be elite level to begin with, making conjugate helpful for a limited number of people.

Dynamic-effort and speed work are not as effective at getting stronger for beginners and intermediate lifters as doing sets of five repetitions and adding weight over time. Linear periodization creates a constant adaptation in strength and increased force production. Doing the compound lifts—the squat, bench press, and deadlift—is all most people will ever need to get strong.

But if you are in the top three percent of all lifters, you may benefit from some conjugate work. There are a lot of specialized movements that help increase muscle bellies that have some carryover to elite lifters. I do believe some parts of conjugate can be applied to all lifting. I encourage everyone who is interested in getting stronger to become a student of the game. Do as much research as you can. The work doesn’t end under the bar—that is just the beginning.

Brandon Heflin

This text was proofread/edited with the assistance of ChatGPT an AI language model (OpenAI, 2025)